Art in the Time of COVID: A Month’s Respite Elsewhere

Abigail Chabitnoy, Poet and Print Maker

Virginia Woolf wrote of the importance of a room of one’s own. In the time of COVID, as businesses shutter and offices look for remote solutions, such rooms become harder to find, our homes smaller and smaller, proximity and isolation combatting for first blood. We are cut off from those around us, and so we have time to write but cannot. We are thrown in 24-7 company with those we love typically on nights and weekends and so our attention is stretched and we cannot write. The news seems intent on outdoing itself with each update and so we ask why should we write and we cannot. But we must. It has always been so and we must.

I left for my residency at Elsewhere Studios a week into the George Floyd protests in Denver, which I was compelled to support in socially distanced solidarity as my residency had already been delayed due to the pandemic, and I had agreed to take necessary precautions so as not to carry any virus to the community that would be my home for June. Eager for this time to work on my next book, a collection of poems that had been accruing even in their neglect for some time as daily demands on my time from work and home took precedence, it was still a strange time to be removing myself further from the world I was in fact trying to understand through poetry. And yet for that very reason it was necessary to do so; it is necessary to continue writing, to continue making art, indeed to prioritize such endeavors in time of turmoil: in order to understand and thus engage sincerely with a world so in need of being seen.

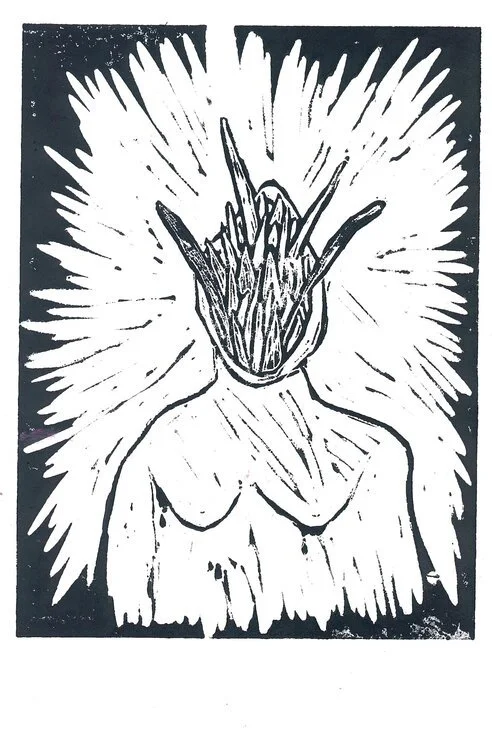

If this post is off to a somber start, blame it on my inner child. I’ve always been too serious for my own good. My first month-long residency was spent agonizing over not producing enough, of too much time spent simply thinking about the work, reading, and simply allowing myself to be. I came to my residency at Elsewhere Studios with a plan and an elevator pitch for my second book: a consideration of violence and narratives of violence as they pertain to women, indigenous people, and the landscape. In some version, I had intended to focus on how this violence is survived, and while there is evidence on survival, it has assumed more the shape of resilience—of defiance. In this manner, I have come to find beauty too in the strength that reveals itself in such defiance. At Elsewhere, I also rediscovered joy in the experience of discovery, of play, of listening to the work instead of speaking. I put the word “print maker” after my name for the first time. (Or rather, Henry Kunkel did, in preparation for my artist talk, and I’ll be forever grateful that he did.)

In preparation of a month of uninterrupted and COVID-extra-isolated time to read and write, I purchased supplies to experiment further with lino-cut block printing, a technique I’d first tried for a broadside a couple years earlier and had been meaning to return to, but couldn’t quite figure out what to make of it. As part of my residency encouraged the production of a chapbook during my stay, I reconnected with language and the space of the page, the medium of the book, in a renewed spirit of conversation and discovery. The result—in addition to a fully formatted second book manuscript, enough poems leftover to begin a third book when I was ready, and a newly conceived chapbook that returned to the lyric roots of my first book while also conversing with historic source materials—was the beginning of a series of prints and images that were only just beginning related to the violence investigated in my manuscript, as well as how to transform such violence.

I’ve been asked since the pandemic how I am responding to these bewildering times in my work. I didn’t think I was, directly. It’s not how I approach my work, consciously. But of course I am. These times might be bewildering in their own unique way, but what time is not bewildering? When has art not been a response to our desire to understand and re-vision our surroundings and circumstances? What else is a series of headless women, of open neck wounds that are both the receptacle of violence and the birthsite of the strength to resist those who would make us victims? In a capital-driven society, in the midst of calls for social justice revolution, as a pandemic makes painfully clear the inequalities and vulnerabilities of our current system, it may at first seem natural to question the wisdom of setting aside resources for illogically minded artists to step out of the world for a space and make art. But it’s in the artmaking we teach ourselves how to live.

I am very grateful for the opportunity to remind myself as much during my month at Elsewhere, and for those community members and conversations I was able to engage with despite the pandemic. It was encouraging to observe how others negotiate this need to be present with this need to step aside and create. And it was rejuvenating to get back in touch with some spirit of play, despite having an inner child that has always thrived on discipline and determination. I’ve already started my next block prints, and can’t wait to see the final results of my chapbook when it’s in print. It’s been said that doctors keep us alive, but artists remind us why we live. So here we are still in the grips of a pandemic, still fighting for a more just and equitable system of living, and we have time to write, and we have no time to write, and we have space to write, and we have none. We cannot write. And we must.

Until next we are Elsewhere, quyanasinaq. Sincerely, thank you.

Abigails intention for her residency:

We tell stories to survive. In my current project I am revisiting the stories we tell—stories of families and relationships, stories of origins, stories of floods, of beginnings and re-beginnings, of our nature, of our history, of our ancestors, of our language, of our gender roles and societal expectations. And while I am revisiting many of these stories in the context of violence against women, against the landscape, and against indigenous people, I intend for the narrative to ultimately illuminate some manner of path forward, some kind of hope—a survival guide, for how to create our own light, how to survive ourselves.

During the residency, I intend to continue to work my way through the Alutiiq Word of the Week Archive, where translated words are accompanied by micro essays that explore the word in context of the culture. I also intend to continue working through various Alutiiq stories and storytelling motifs, as well as popular Western folktales and superstitions. I would also like to revisit additional Carlisle Indian School records and student accounts, as well as archived interviews with Alutiiq tribal elders to broaden the scope of survival narratives. When asked by settlers if the world would end, the Alutiiq people responded, no. I am choosing, through poetry, to gaze unflinching at the world in all of its complexities, all of its faults and failures, all of its violence and injustice through a lens of survival and resilience, through story, to provide space for a self that is multiple and ever beginning. Because the truth about our stories is that’s all we are.