Tracing Ancestral Footprints from Elsewhere to Here.

Rebecca Nava Soto

During our summer at Elsewhere's artist residency, my family and I found respite from the routine of the Midwest, immersing ourselves in captivating landscapes. Upon our initial arrival, the mountainous scenery prompted continuous expressions of awe, gradually we accepted and integrated the beautiful surrounding tapestry as our new normal.

This residency served as the launching pad for my exploration into "The Land Returns" project, a quest, in part, to reconnect with my indigenous Mexican roots in southwestern Colorado.

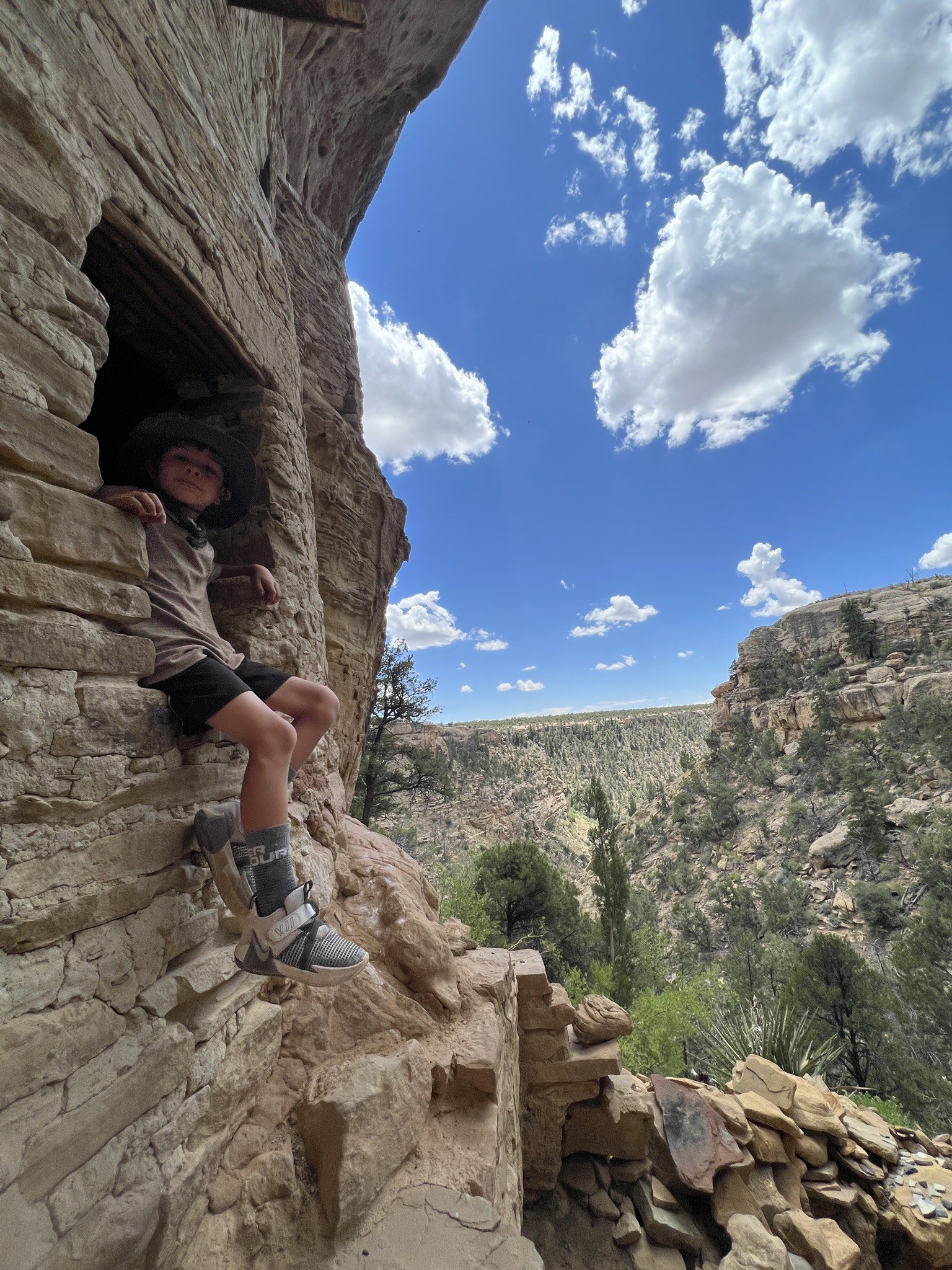

With Elsewhere as our hub, my family and I embarked on expeditions to the Black Canyon of the Gunnison River, the Uncompahgre Plateau petroglyphs sites of the Shavano Valley, the Mesa Verde National Park Cliff dwellings and the Spectacular Cliff Dwellings and petroglyph sites at the Ute Mountain Tribal Park.

There, we traced the footsteps of the Uto-Aztecan people, from which one band journeyed from these origins 5,000 years ago and into the Valley of Mexico in 1064 A.D., ultimately evolving into the Culhua-Mexica or Tenochca people, the ancestors of the Aztecs.

Engaging with this captivating history and the scenic allure of tourist spots, a stark absence of indigenous presence outside the Ute Reservation area is glaringly obvious. It reverberates a disheartening disconnection from the land's original stewards. Instead of indigenous vitality, tourists and the descendants of colonizers revel in the land's offerings—breathtaking mountains, stunning deserts, abundant agriculture, craft beers, ski towns, horse farms, and crystal shops.

Amidst the breathtaking rugged scenery of the tribal park with my family, I grappled with conflicting emotions. Our Weeminuche guide, Wolf, shared some of the brutal history of his family and community's experiences with national parks and the U.S. government. The juxtaposition of otherworldly landscapes and the unsettling truths of forced relocations, diseases, and cultural suppression created a poignant internal conflict. Keen on averting the grasp of depression, I continued to investigate these realities, navigating the delicate balance between appreciating the moment with my family and confronting the somber history and present day indigenous challenges.

In my studio at Elsewhere, I found a creative space to process my experiences through painting, collage and ephemeral studies. Interestingly, it wasn't until after receiving the residency award that I discovered Terrence McKenna's former apartment would be my unexpected sanctuary. I found comfort in this cosmic wink and in our cool hovel where the walls echoed with the wisdom of a writer, mystic, and ethnobotanist whose work has been my intellectual compass for the past few years.

As the Midwest autumn chill creeps in, my children and I, giggle out loud recounting summer tales of our time with our residency family, a lovable crew featuring Megan, Lena, DW, Jimmy, (with special appearances from sister Olivia and partner Ben) and, of course, the unforgettable goof troop—Henry, Ramona, Simone, Tenoch, and Paloma. Sweet childhood (and parenthood) memories etched with horse camp escapades, daring zip lines, rejuvenating swims in the North Fork Gunnison River, stargazing on the mesa, shared meals, bonfires, and silliness that bound us together.

Here in my Ohio studio, I find myself expanding on the seeds of research planted during our Colorado residency. The echoes of honorable ancestors evoke a poignant moment, urging reflection and reconciliation with the past.

Remembering that surreal landscape, made of memories sourced from interior and exterior investigations. Research is met at a hinge point with guiding synchronicities and moments at the vortex's edge. Tugging at my curiosity, beckoning me towards more courageous participation in the studio and in life.